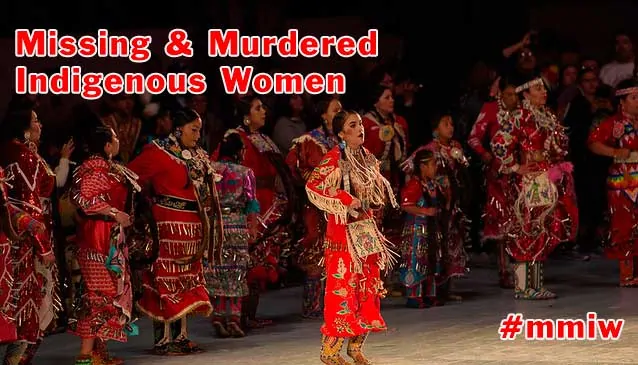

While violence against women plagues many communities across the country and around the world, the Native American indigenous groups in North America are particularly hard struck by this devastating problem. Missing and murdered indigenous women (MMIW) present some of the highest statistics for violence and death in these areas. The situation has existed for generations and continues to harm and destroy individuals and families to this day.

While many awareness programs and initiatives exist to attempt to stem the rising numbers of cases of violence, missing, and murdered women in indigenous communities, far too many are still suffering at the hands of others. The statistics are sobering, to say the least.

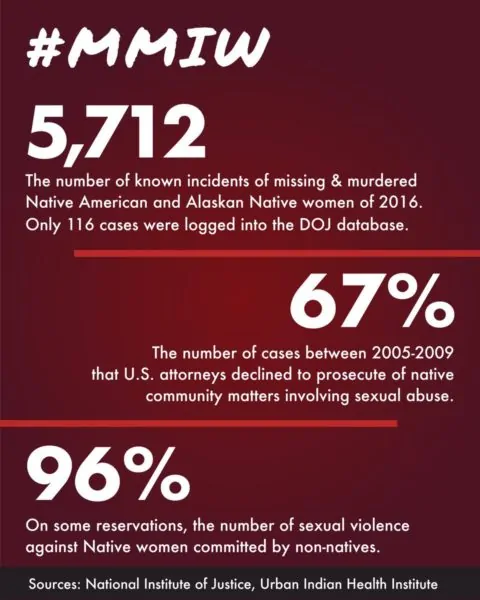

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Statistics

The US Department of Justice maintains records on murders every year across all demographics of men and women in the country. When it comes to indigenous women, they are 10 times more likely to be killed than the average national murder rate. Despite how high these statistics seem, they cover only a small percentage of all of the native women who are victims of violence every year. After all, the majority of violent crimes do not end in murder. Nevertheless, they are incredibly prevalent in indigenous areas.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Native American women under the age of 35 experience a higher murder risk than many other groups. It is the third or fifth most prevalent cause of death for girls and young adults from age 10 up to age 34.

One of the most difficult things when learning the truth about MMIW is that statistics are extremely hard to come by. Various studies, such as one by the Urban Indian Health Institute or UIHI, of attempted to gather information from all across the country and compare it to official statistics from ordinary law enforcement agencies and other groups. The numbers, such as a total of 5712 cases of missing and murdered indigenous women, focus primarily on people living off reservations or native land. Nevertheless, it seems shocking to find that only 116 of those cases wherever included in the US Department of Justice's official missing persons' lists.

As expected, the highest rates of murderers and missing people reports occurred in western states with the highest populations of Native American people. These include New Mexico, Washington state, Arizona, Montana, California, and Alaska. Far too few of these cases are ever solved. Even when the law enforcement agencies come up with a ruling, it frequently fails to satisfy the families and communities of the missing or deceased women. In Canada, CBC News has undertaken a study to find out the truth about more than 200 cases. The data shows that the problem grows worse as the years go on.

While the numbers may shock and dismay us, the high rates of killing and kidnapping indigenous women are so much more than a devastating data point on the crime charts of this nation. The problem has existed for generations, and very few things are being done to solve it. The complexity of the issue is as deep and wide as any other crime issue in the United States today. In order to begin to understand why it exists and what can be done about it, you must look back in time to the history that surrounds the serious problem of missing and murdered indigenous women statistics.

History of the Issue

As difficult as current statistics are to find about the total numbers of missing and murdered Native American women, historical data is even less available. While numbers from the above-mentioned study from the Urban Indian Health Institute and data from the National Crime centers show more than 5,000 missing indigenous women every year since 2016, other statistics from individual states, communities, and even Canada seem to augment this number considerably.

Women in all cultures have historically been the target of violence more than men. In Native American communities that have experienced a high degree of additional problems due to colonialization and the resultant prejudice and economic difficulties, these problems are made worse. There is a considerable psychological effect on both individuals and entire groups who are continuously downtrodden, dismissed, and denigrated for generations.

The lack of clear information shows a deep-seated problem that speaks precisely to the history of the missing and murdered women statistics. Far too many of these crimes are dismissed as simple domestic violence issues and go unreported, uninvestigated, and unsolved.

Why This Problem Exists

Unfortunately, it seems that racism and disregard for indigenous peoples, in general, may have a lot to do with the lack of solutions for the MMIW problems that plague communities all across our country today. When speaking about violence against women, kidnapping, and murder, two generalized groups emerge. One portion of the victims was affected by domestic violence and hurt at the hands of someone they knew while the others were victims of more randomized acts of violence. In the Native American communities, far too many instances of both exist.

Extreme problems like this frequently wind back through the generations in an attempt to discover their source. From the very beginning of cultural interactions between natives and non-natives in the United States, many outsiders viewed the indigenous people as less than. There is a history of slavery, extreme violence, cultural eradication, and attempted destruction of entire tribal communities and the people associated with them.

There is no doubt that the idea that an individual is somehow better or more worthy than another can lead to violence, exploitation, and murder. The geographic locations where natives and non-natives interact seem to breed more violence as well. This is especially prevalent in places close to the Mexican border where indigenous people may be frequently mistaken for a criminal element simply because of the color of their skin and hair. In a nation overcome by these attitudes, it is easy to see how they hate and disregard trickles down from the top to influence individual violence.

The high rates of missing and murdered indigenous women also occur because law enforcement and the organizations supposedly formed to help victims of violence do not put an emphasis on the problem. With only 116 out of 5700 crimes ending up in the DOJ's database, it is quite easy to see that the general attitude about indigenous crimes against women is simply not conducive to solving the problem.

Statistical gathering methods may also contribute to the lack of appropriate information about MMIW. Victims may be misclassified as white or Hispanic instead of Native Americans. Even those properly identified may not have ties to a particular tribal group, which creates a lack of knowledge for particular communities to solve internal problems. The very fact that more Native American women go missing or murdered even contributes to the attitude that they must put themselves in harm's way more than other people.

Things like higher levels of poverty, addiction, unemployment, and nonviolent crime also contribute to violence against women in indigenous communities. These things seem to go together in many demographics across North America. Finding a solution to these problems has been insurmountable since the beginning of the country, it seems. However, individual and smaller group efforts are constantly pushing up against these types of problems that affect women, men, and children in native groups.

What Is Being Done To Help Native Women?

One of the most effective ways to minimize the rate of missing and murdered indigenous women as a whole is to push for accurate data collection and handling. Understanding the problem can go a long way to solving it or minimizing its effects on this troubled group. Unfortunately, it seems that the victims of these violent crimes cannot count on the largest national or even state organizations in many cases. Whether it is caused by institutional racism, lack of funding to serve these communities, or simple laziness, and minority of non-official people can do little to change the process.

That being said, there are definite changes in the works across the United States. In 2019, the “Not Invisible Act” was put before the Senate. It outlined the incredibly high rate of violence within the American Indian communities, statistics about poverty, unemployment, and homelessness, the truth about MMIW, human trafficking, and other criminal issues. The goal of this act was to improve how government agencies identified indigenous crime and reported it accurately.

The year before in 2018, another bill was passed and became “Savanna's Act.” The specifically focused on missing and murdered indigenous women, the underreporting of these crimes, and pushed for additional coordination of law enforcement agencies to both record data appropriately and attempt to solve the crimes. Although it struggled to get past due to funding issues, it was eventually adopted and put into place. The name of this act comes from a woman named Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, who was kidnapped and murdered in North Dakota in 2017. She was pregnant at the time.

Although not specifically focused on missing and murdered indigenous women, the 2013 “Violence Against Women Act” also includes a provision specifically geared toward Native American women, children, and elders. While it reaffirms the fact that the tribes themselves have jurisdiction over these crimes, it also pushes for additional measures to take them seriously. After all, women go missing and are murdered often as an end result of other types of violence that escalate.

More often than not, the actions taken to improve the chances of indigenous women at avoiding these types of violent crimes are being done at the grassroots level. Also, tribal organizations themselves or working as diligently as possible to minimize these issues in their own communities. The wheels of justice grind slowly, and far too many women will go missing or get murdered before this problem can be solved once and for all.

With the complexity of the issue and its association with the in action or erroneous action of law enforcement agencies and government entities, it can be difficult to figure out how you can do anything to minimize the serious problem. Several efforts have been taken in the past few years and continue to be organized to show solidarity, give support, and fight against the injustices that put indigenous women at risk every day.

How Can Everyone Help?

The rumble of more than 100 motorcycles carrying messages of hope, support, symbolic red flags, and bundles of sacred plants traveled for more than 12,000 miles across the United States and Canada in 2019. This Ride for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women was an opportunity for people to get the word out about the incredibly high rate of these crimes within the Native American communities. The route itself is shaped like a traditional Native American medicine wheel. Only two of the riders are traversing the entire thing as the others, obviously, need to work and take care of their families.

Rides like these and other initiatives are primarily about raising awareness and spreading information. The bikers wearing the “No More Stolen Sisters” flags will also leave informational pamphlets where they stop and post important information and progress reports using the hashtag #RidingForMMIW.

The color red has been adopted as a symbol of this movement. It is traditionally a color associated with spirits in many indigenous cultures. The #MMIW campaign includes many different individual groups and events to get involved with.

Other events across North America occur all the time to support MMIW and anti-violence initiatives in the Native American communities. A woman named Marita Growing Thunder in Washington uses her native artwork and ribbon skirt making abilities to raise awareness about the high rates of murder for women in indigenous communities. Two of her aunts were murdered, one in a domestic violence incident and her grandfather's sister was killed by a police officer.

Community databases like It Starts With Us are building to raise awareness and fill in the gaps that law enforcement agencies create. Newspapers, television programs, and Internet websites host shows and series about missing and murdered indigenous women with increasing frequency. A recent project from the Seattle Times tells the stories of just some of the women who have lost their lives to the high rates of violence.

If you feel compelled to help fight against the serious problem of missing and murdered indigenous women across the United States and Canada, your first task is to learn all you can about the problem. Study not only the official statistics shared by law enforcement and justice agencies, but look deeper into smaller studies, tribe-based information, and the types of things that people gather on their own. The more education you have about the truth, the more you can discover ways to make the high statistics go down.

The next step is the education of others. For far too long, the problems of violence, kidnapping, human trafficking, modern slavery, and murder in native communities have been swept under the rug, ignored, or dismissed due to long-held racist and prejudicial attitudes. Learn the appropriate hashtags and get involved in spreading the word on social media. Take part in local or national events that stand up for the rights of women and attempt to raise money to serve them. Stamp out prejudice whenever you see it.

Consider more hands-on help by volunteering your time or resources directly to organizations, groups, or individuals affected by this serious problem. If you are a psychologist or other type of therapist that interacts with people affected by missing and murdered indigenous women issues, make sure you know how to approach the unique cultural issues associated with the problem.

In many ways, you can help promote justice for native women and help stem the tide of missing and murdered indigenous women by identifying who is making the biggest difference and supporting them. Whether this is calling or sending letters to your state representatives to convince them to support federal bills or choosing a reputable charity for your monthly or yearly donations, you can find ways to help that fit your particular circumstances.

Entire communities of indigenous people struggle with an epidemic of MMIW. What little statistics exist shows an unfortunate uptick in the rates of murder and other types of violence. With roots in attitudes and practices that stretch far back through history, it is not an easy problem to combat. However, with a fervent desire to help, effort and funding, there exists a very strong hope that the accurate statistics will soon show a downward trend in the numbers of missing and murdered indigenous women.

Robert

says:“Women in all cultures have historically been the target of violence more than men.” This is only true in regards to being exposed to a larger VARIETY of crime. Rape, Sexual Assault etc. Men have always traditionally suffered more from violent crime and violence overall.

B. Bailey

says:I have been following this, and feel sad and sick over it. think it is important to gather data on how many of these murdered and missing women and girls are a direct result of pipeline and extraction industry “man camps” and fossil fuel trains that go coast to coast, where many of trafficked girls, women, and boys are shipped out to foreign lands. How would we go about gathering that data?

I can’t find any data about MMIWG since the 2017 report – and none on the extractive industry’s toll on them, though I’m certain that it is a HUGE contributor in a growing industry that is ravaging all the lands it touches, everywhere and especially on Indigenous lands. It seems important to connect the dots between crimes on Indigenous women and girls and crimes on Mother Earth. I also wonder what percentage of men doing this are white? I ask this because, as a white woman, I have yet to ever meet men of color who work for these industries – so I think it’s a white colonization thing.

Is there a way for people to report their missing, having to do with these extractive industries, so we can start gathering this data? My heart goes out to everyone who has lost a mother, sister, daughter, or son to this sickening and horrific issue.

big brain

says:Thats cap

Eden

says:I’m using this article for an essay I have to write for my college English class. I’m planning on being a lawyer to help people and to bring justice to others. I know I’m one person but I believe that I can make a change, and if writing this essay is the first step, this will be the best essay I will ever write.

Thank you for shedding light on this horrific situation.

Sue Shunatona

says:Very informative article. Thank you.

Paco Pelletier

says:A good article on such a sad problem. Those who harm, prey on or traffic those who are smaller or physically or mentally weaker are predators. Those people are not fit to live in any society other than a penal society, for how ever long they live.

ROY Weaver

says:I DID NOT GET A EMAIL TODAY SATURDAY 11-23-19 TIME -9:42PM.

Tracy Coppola

says:I can’t read anymore. I’m getting sick to my stomach. Definitely will do research to find out how to best to get the word out. Count on my donation. God sees EVERYTHING. He will get His vengeance in His time. Weeping endures for any evening but joy comes in the morning.