The cases of ethnic fraud in academic institutions—mainly being reported in Canada—have started many conversations over how to prevent people from claiming an Indigenous identity that doesn’t belong to them.

While there have been a handful of high-profile cases, it’s not an issue that registers as a priority among many communities. Purposely claiming a false ethnic identity to get ahead in academia takes away opportunities from actual Indigenous people in the upper echelons of institutions of higher learning, something many Natives don’t have access to.

Natives are also impacted by fraud and missed opportunities in entertainment, arts and crafts and fashion. The high-profile stories reported in the media usually only highlight those holding prestigious positions though.

Money is usually at the root of why suspicions are raised to begin with.

However, the often dubious process of hunting down potential perpetrators of ethnic fraud can also have negative consequences for actual Natives. Many of these cases begin with Indigenous colleagues questioning the validity of another’s identity. In some cases, anonymous correspondence was sent with allegations. There are even social media accounts dedicated to sniffing out “suspicious” claims.

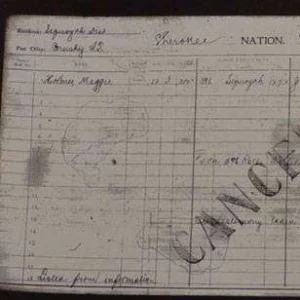

Somehow a genealogist gets involved and either confirms or denies a person’s identity. After this information is presented to employers, there’s usually a push for termination and hiring process overhaul in order to prevent the colonial practice of white people stealing Native identities in the colonial institution of academia.

But what happens when actual Natives are targets of suspicion of ethnic fraud? During the so-called “pretendian list” debacle, Natives were publicly named and implicated in identity fraud without any retractions or accountability. The fallout from these types of harmful actions is that Natives are now being asked to prove their identities. Whether it be from random social media users or legacy media outlets requesting enrollment information, the trajectory is leading to a dark place.

Who decides that someone should be investigated? Absent any input from legitimate leadership of a tribe or nation regarding a person’s identity, we’re left with unofficial committees of roving amateur genealogists with an Ancestry.com account. The natural course of “pretendian” hunting circles right back to upholding colonial practices like blood quantum and federal recognition. There have even been suggestions that the federal government criminalize offenses on our behalf, without recourse for Natives who were adopted out, disenrolled or don’t meet blood quantum requirements in their respective tribes and nations. Many Natives are also from multiple tribal backgrounds but only allowed to maintain official citizenship (enrollment) in one tribe/nation.

So we’re back to square one. Sovereign tribes and nations set the requirements for citizenship. That is where these issues need to begin and end. If academic institutions were serious about Native representation and not tokenization, they would be communicating with Native leadership and fostering relationships with those communities. Instead, they hire random people all willy nilly to check a box.

Many institutions at the center of ethnic fraud scandals also claim they aren’t hiring based on identity, making it harder to hold them accountable.

There should also be as much concern about the livelihoods of small Native businesses and independent artists as there is for policy-shaping and public-facing folks. Non-Native websites and large industries alike are notorious for stealing artwork and designs from Native artists and crafters. These issues don’t make headlines because it doesn’t impact those with the loudest voices and biggest platforms.

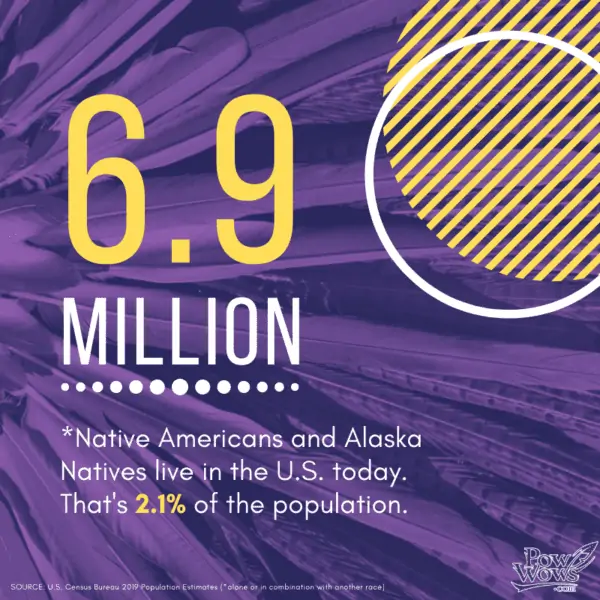

Ultimately, all discussions of ethnic fraud lead back to the elephant in the room: Indigenous people are the only groups in America who are issued documents listing our “degree of Indian blood.” While many Natives are staunchly against blood quantum, it becomes a necessary evil for some in order to remain part of the club—upholding colonization.

There’s not currently a clear solution for solving the issue of ethnic fraud because we either need to submit to systems that have harmed us for generations or stand before tribunals of self-appointed gatekeepers. While it’s important to address individuals deliberately faking Indigenous identity for monetary gain, avoiding inflicting harm on our communities in that process needs to be a top priority.

This can’t exist without colonial practices such as blood quantum and “federal recognition.”

Do we submit to a tribunal of anti-Black aunties vying for a spot on the local bookstore list?