One of the most painful truths in the history of Native Americans is the forcible removal the children.

Sadly, indigenous children are disproportionately represented in the United States foster system—1.9 percent of indigenous children wind up there, compared to just 1.3 percent of the general minor population. Those numbers are the highest in Minnesota and Oklahoma.

The removal of indigenous children has devastated tribal communities for generations, causing huge disconnect, loss of identity, culture, language, and family.

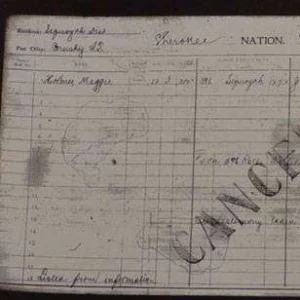

According to the data compiled by the National Indian Child Welfare Association (ICWA), 80 percent of indigenous families living in reservations have lost at least one child to the foster care system and although the Indian Child Welfare Act has existed since 1978 and gives the respective tribe authority over custody proceedings, the number of indigenous children affected far surpasses any other racial or ethnic group. Furthermore, 85 percent of those children are sadly placed outside of their tribes or relatives—leaving these children lost and questioning their identity.

The issues indigenous children face today are tied to horrific systemic oppression of the past—loss of land, displacement to reservations, broken treaties, loss of language, and lack of protection and support by state or federal laws. The actions of the past fueled the belief that indigenous people cannot take care of themselves because they were seen as “less than” by white society. As a result, government agencies felt the need to intervene and overreach.

We’ve seen this play out with thousands of children who were removed and placed in residential schools and continue to be moved into the foster care system. This has contributed to generational trauma affecting the dynamics of the family unit—leaving each member of the family dealing with mental, emotional, and psychological issues that never healed and in some cases, domestic abuse, physical and sexual abuse and drug addiction.

Furthermore, the ICWA established certain laws that required Native American children to be placed in homes that have ties to a set tribe and reflect Native American culture. However, this effort falls short since, many times, state and federal law can hinder tribal court decrees.

According to Takesha Allen, Director of Case Management at Kessler Institute for Rehabilitation who previously worked as Director of Residential Services for YWCA in Union County, New Jersey, which is the lead domestic violence agency in Union County, states one of the biggest issues people of color and indigenous people face is the cycle of violence and poverty. The underlying intent is to keep the children safe and keep them with the non-offending parent regardless of the poverty level or psychosocial issues; however, due to lack of knowledge of tribal sovereignty laws, Native culture, and language, many social workers and outside forces overstep and strip parents of their rights.

Research shows that indigenous children have an extremely difficult time transitioning after emancipation. Many end up living on the streets, suffer from addiction and unemployment or become incarcerated. Furthermore, many children who age out of the system find it difficult to return home since they have no connection to their family or tribe.

The Split Feather study conducted in 2000, found that indigenous children adopted as infants become emotionally wounded adults with psychological issues stemming from lack of identity and cultural ties. According to Allen, state and local programs should collaborate with Tribal Nations, and make a more concerted effort to help youths transition from the foster system into the community. Tribal leaders and programs should promote tribal enrollment, education specific to each tribe, cultural activities, and coming-home ceremonies to help adults feel connected. The goal is to prevent further re-victimization and generational trauma by providing assistance and decreasing the likelihood of incarceration.

The federal, judicial, and legal system has been used far too long as a tool of oppression that affected not only how we see ourselves, but how others see us. This past November, CNN labeled indigenous people as “something else” rather than explicitly including us in the election process. Lack of visibility and inclusion in media, education, healthcare, legal systems have played a key role in the erasure of indigenous people in the modern world, causing people to see us as caricatures, mascots, and the like. If we are not seen as vital members of society who can thrive, create, and enhance other cultures and communities, we will be erased, and this erasure affects our most vulnerable members: our children.

Indigenous people have the right to demand to be seen and counted. We have the right to have a system where our children aren’t stolen and then shunned when they try to return. The foster care system may be a lifeline for some, but for Native people it has been a noose.

The foster care system needs to recognize the unique demands of tribal communities in order to keep children with their families and tribal communities by implementing better models of care and education to case managers who specifically work with the indigenous community. The foster care system should not be the new residential school system.

We must refocus our efforts on better outcomes for Native children.

Last Updated on August 2, 2021 by Paul G